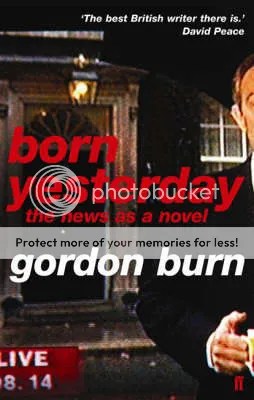

The cover of Born Yesterday quotes novelist David Peace calling Burn “the best British writer there is.” Peace and Burn have a certain sensibility in common so we might expect some bias, but even so, at times I would agree with him. Burn’s relentless pursuit of the centre of “the psychopathology of fame” over the last couple of decades has given us some wonderful, overlooked books. His debut novel Alma Cogan (1991) took a subtle look at the tabloid iconography of Myra Hindley while Rupert Thomson was still in short trousers. His last book Best and Edwards was my favourite read of 2006, bringing an exceptional literary intelligence to twin tragic tales of the other end of celebrity: a book about football which even a soccerphobe like me could love. So when I heard that he was going to be taking the major news events of 2007 and making a novel out of them, I was hyperventilating with anticipation. My usual trawls of eBay, publisher’s publicists and elsewhere at the start of the year for an advance copy proved fruitless; no wonder, as it turns out Burn only started writing it at Christmas, and finished just six weeks before publication, in mid-February. A novel in six weeks? Are you thinking what I’m thinking? Iain Banks. Oh dear.

Here’s the news: it’s not a novel. There is no overall storyline, and no invention at all so far as I could tell (even the joining character, ‘he’, turns out to be Burn himself, researching the book). Stylistically it’s indistinguishable from Best and Edwards, which means it has a ruminative air, circling its subject matter with facts and implications, and always returning to Burn’s bête noire: the public appetite for pointless fame, the media happy to feed it, and the effect it has on consumer and consumed.

Also like Best and Edwards, Born Yesterday is not ashamed to admit when someone else has said something better than Burn could – or before he could – and the book is rich with aphorisms from reliable sources:

There are really two kinds of life, notes the American writer James Salter. There is the one people believe you are living, and there is the other. It is this other which causes the trouble, this other we long to see.

Salter joins J.G. Ballard, Philip Larkin, George Steiner, John McGahern, and names new to me, all with something to say on this psychopathology which so fascinates Burn (and me, otherwise why would I be writing this?). Howard Singerman: “The collective memory of any recent generation has now become the individual memory of each of its members, for the things that carry the memory are marked not by the privacy, the specificity and insignificance of Proust’s madeleine, but precisely by their publicness and their claim to significance.”

But where does this leave the meat of Burn’s book, the news stories and people we think we know from the current affairs of the past summer, as we wait patiently for him to transform their base stuff into art? It doesn’t happen, quite. The main players are Tony Blair as he hands over his premiership to Gordon Brown (with his “folded Shar Pei features”), the bombers of Glasgow airport and instantaneous media hero John Smeaton, and Kate and Gerry McCann, parents of Madeleine McCann “who vanished into folklore and common fame” on holiday in Portugal.

Burn treads carefully with the last, justifying their inclusion in the book on the basis that their media story is one of manipulation at both ends – and I bet he wishes he’d held the deadline back a few weeks to cover the McCanns’ libel victory against Express newspapers – for reasons fair and foul. It’s also clear he couldn’t resist it because of the parallels of the McCann story to some of the content of his 1995 novel Fullalove, which he explicitly reminds us of (to be fair, most of us probably needed reminding), as well as some inconsequential connections with other elements of the book (Proust/madeleine, defective eye/Gordon Brown).

There’s the odd bit of flashy prose which is even more reminiscent of Fullalove, when Burn engages with the garish elements of urban modernity (“…on the top of the number 19, gazing out of the tagged, hazed window, catching the effervescent blue of the digitised sign on the side of the bus occasionally bubbling up against shop window displays and stretches of marble curtain-walling…”), and the fiction comes really only when he extrapolates into the lives of people he sees, such as the woman in the supermarket buying “a slippery stack of New!, Now, Star and other junk magazines” and an addict’s supply of chocolate bars:

this innocent but potentially sordid transaction – the basement living room, the gorging, the trips to the bathroom, back to New! and EastEnders; a woman scoring her drug of choice at the local Tesco.

Again the most succinct summing up of the problem with the sort of fame we are now exposed to, comes from another writer, this time Thomas de Zengotita. It could equally apply to the benighted state of our bookstores, where actress-slash-model-turned-author gets more shelf space and print coverage than fine writers like Burn.

Real heroes today must become stars if they are to exist in public culture at all. That is, they must perform. But as soon as they do that, they can’t compete with real stars – who are performers.

What timing Mr Self. I was just browsing through some Gordon Burn books yesterday, I came to them via Rupert Thomson! But I just couldnt work out whether I would like them or not. They seem quite peculiar as novels, or not novels go. Would you recommend a best place to start with him?

It’s hard to say jem; although I think Burn can more or less do no wrong (but Born Yesterday isn’t his best), I suspect he is a bit of a Marmite author whom you either love or hate. Of the three other novels – Alma Cogan (1991), Fullalove (1995), The North of England Home Service (2004) – I’d recommend Alma Cogan.

Of his non-fiction, two are ‘true-crime’ (but only in the sense that In Cold Blood is true crime) – Somebody’s Husband, Somebody’s Son (1984) about the Yorkshire Ripper, Peter Sutcliffe, and Happy Like Murderers (1999) about the Wests – I haven’t read the latter, which I understand to get pretty grisly in places.

His other two are sports-based: Pocket Money is about the 1980s snooker scene – it was his second book, published in 1986 but has just been reissued and I picked up a copy this week. Then there’s Best and Edwards (2006), which I think has a strong claim to be his best work. Please don’t let the fact that it’s about footballers put you off – it’s so much more than that! I read it pre-blog but I posted an Amazon review at the time.

So in summary: Alma Cogan and Best and Edwards!

Thanks for a great walk-through. I always find it very daunting to know where to start with a new author, and so many times I pick one and then don’t like it and then someone says, ‘oh, thats a bad one, all the others are great’!

I did a lot of murder reading in my teens : ) so I’ll pass on those for now, but I’ve added ‘Alma Cogan’ to my lists. I’ll report back on my findings.

I thought Born Yesterday was great: interesting and written at an important time. Not a perfect book, but then it was never going to be after that 6 week writing period. I think the importance is possibly yet to be realised but with debates going on all over the place in terms of the future of news: the rise of citizen journalism, the lack of trust people have in traditional news organisations, the civic role that news media has in society; it’s really timely.

By writing about news events at a distance Burn draws together threads and parallels which aren’t spotted at the time because of a lack of perspective. Some of those coincidences don’t really hit the mark (Madeleine McCann and Marilyn Monroe having the same initials, say) but the drawing together of news strands is a really interesting exercise. Perhaps this is the role of the professional journalist in the future: the citizen journalists collect the fragments and the journalist sticks them together into the whole.

I thought there were some interesting parallels in terms of form with BS Johnson – ie the novel as something other than fiction. None of Johnson’s book really worked, of course, but as experiments they are fascinating. Strange that as a journalist himself Johnson didn’t have a similar idea himself. Maybe he would have gotten around to it eventually.

The other great value in the book is Burn’s sympathetic writing about celebrity and media, which is excellent – his coverage of the McCann disappearance is thoughtful and balanced.

Oh, and I kind of assumed the bits about Thatcher in the park were made up, but maybe I am wrong.

Interesting discussion at the Guardian about this book.

Thanks Dave. Yes, you’re probably right, I’m sure the Thatcher stuff is invented. The greatest thing about Burn’s book, apart from the sheer pleasure of nestling into his worldview again so relatively soon after his last book, is indeed the idea. Amazing really that nobody has thought of it before. Perhaps the novelty aspect alone will give Burn a boost in the public consciousness.

The Guardian have also reviewed this as part of their Digested Read series.

Thanks k., I read that with a minor feeling of despair as I hate the blanket cynicism which John Crace brings to his Digested Reads. It’s a bit like the book reviews in Private Eye: when they seem to hate everything, it devalues their opinion. If they mentioned something they liked from time to time, it would make a big difference.

I too hope that this book will give Burn a boost in the public consciousness. When he spoke at the Belfast Festival last year on Best and Edwards I was dismayed at the how few people were there to hear him. Even the literary luminary introducing him, pleasant though he was, didn’t seem particularly well informed about Burn and his oeuvre. I had a short but delightful conversation with the man; so pleased was I to have met him that I bought a bottle of champagne on the way home. (Duncan Edwards must surely be the most wholesome thing Gordon Burn has ever written about.)

I thought Burn’s treatment of the McCanns in Born Yesterday was measured and perceptive. I found more insight in the very brief Gerry McCann / Roy Keane analogy than in all of Anne Enright’s writing on the McCann parents. The lack of plot and character didn’t bother me; it patterns flux in an interesting way – that’s enough, for me at least.

Yes, Happy Like Murderers is grisly in places but it’s brilliant.

Well Wendy, I was one of the few at the Belfast Festival for Best and Edwards – though as you say, the whole thing seemed geared toward the Best aspect rather than the Burn one, so no doubt if lots of Geordie B fans had turned up, they would have been disappointed by all Burn’s (fascinating) talk of the arc of celebrity and references to Roth and Updike. I went to that reading half-heartedly – thinking not even Gordon Burn could interest me in a book about football – and left it with a spring in my step, and as I mentioned above, Best and Edwards became my favourite book of that year.

Ha, true! I still haven’t read Happy Like Murderers and don’t intend to anytime soon, but I did pick up the recently reissued Pocket Money, which has me fizzing with excitement at the thought of a favourite writer on a favourite subject (snooker, in case anyone’s unfamiliar). I have to temper that with the knowledge that it was one of his earliest books and don’t expect it to match up to the later stuff.

Shocked to hear that Burn died last week from cancer, aged 61. If you haven’t read this poet of ‘the psychopathology of fame’, then I strongly recommend Best and Edwards, referred to above.